I recently had a passionate debate with a German friend about whether Islam lies at the root of the dysfunction in Islamic societies and whether it can be reformed. Like many of my privileged Western liberal friends, his understanding of the Islamic world seems to rest on a brief visit to the Egyptian pyramids and perhaps a guided city tour through Istanbul. He offered the usual well-meaning but tired arguments I've heard countless times. When I asked whether he had read the Quran or the Hadiths, he admitted he hadn't yet insisted that Islam wasn't the problem—it was merely a matter of interpretation. He proceeded to recite the familiar affirmations that most Muslims are peaceful, that Christianity, too, had a violent past, and that the Jewish and Christian scriptures were no better than the Quran.

Not long ago, I would have grown impatient with this confident display of theological, historical, and cultural ignorance. But over time, I've learned to remain composed. After years of dealing with modern Orientalism and the soft bigotry of low expectations, I've decided to become the most annoying educator of these oblivious, suicidal fools. I am convinced—beyond doubt—that Islam has become the most dangerous ideology of our time due to its theological impossibility to reform.

Claiming to be more than just a spiritual path, Islam explicitly defines itself as a perfect, final, and all-encompassing truth. Sura 3:7 states that only Allah knows the true interpretation of its verses—effectively closing the door to human reinterpretation. Sura 5:3 states that Islam is a perfected religion. Sura 11:1 describes the book as flawless in wisdom and clarity, and Sura 2:2:16 denies the human ability to judge. These verses assert divine authorship and inaccessibility; thus, the Quran cannot be altered, questioned, or reinterpreted. It is a closed loop impervious to reform.

There is a persistent attempt among Western thinkers and Muslim reformists to divide Islam into a spiritual, peaceful Meccan phase and a later, political Medinan phase—as if we could somehow return to that early innocence. But this argument dissolves under scrutiny. The Medinan chapters of the Quran, where Muhammad gained political and military power, are not just an addendum—they represent a doctrinal shift. A quarter of the Medinan Quran focuses on Jihad, 21 percent of the Bukhari Hadiths revolve around warfare, and two-thirds of the Sirah—the biography of the Prophet—is concerned with conquest. These are not marginal themes; they constitute the doctrinal core. Muhammad's first thirteen years in Mecca earned him a measly 150 followers. It was only after he embraced Jihad in Medina—using violence as a method of proselytization—that Islam began to spread rapidly. Without Jihad, there would be no Ummah, no Islamic civilization as we know it.

Another persistent fallacy is the conflation of moderate Muslims with moderate Islam—a dangerously misleading confusion. We should indeed be thankful that most Muslims are morally better than Muhammad and choose to live peacefully. But this has no bearing on the doctrine itself. Most so-called moderate Muslims do not follow Islam as mandated in the Quran and Hadiths. They either ignore or reinterpret the Medinan verses and, in doing so, practice a private, unofficial version of Islam that has little to do with its canonical form. Islam, however, defines itself very clearly. It is not up to individual Muslims to redefine it. The belief that personal conscience can override divine decree is, in fact, antithetical to the very structure of Islam.

This brings us to another challenging barrier to reform: the absence of central authority. Unlike Catholicism, Islam has no Pope, council, or classic hierarchy. Reformers are isolated and delegitimized and almost always condemned and hunted as heretics or apostates. Millions of arbitrary fatwas have been issued with impunity by self-proclaimed Imams who wield considerable influence without accountability. This fragmentation does not support pluralism; it legitimizes a thousand versions of unreformable Islam, each clinging to the same foundational triad: Sharia, Jihad, and the pursuit of conquest.

Islam is not merely a religion—it is a civilizational engine built for expansion, powered by a self-replicating mechanism of subversive proselytism through da'wah and dominance through Jihad. It maintains its structure by crushing dissent via apostasy laws and securing internal cohesion through communal pressure and legal entrapment. It is not a belief system in the Western sense of private faith but one that leaves no room for individual liberty or theological reflection. Reform requires self-critique. But Islam, by design, does not allow it.

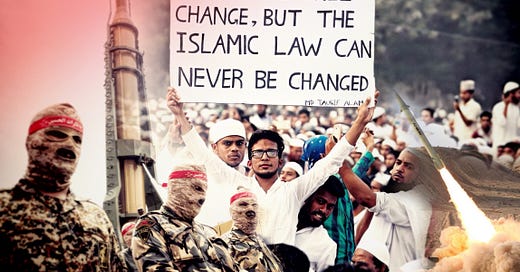

History, like the stock market, does not move in straight lines. It operates in cycles—and political Islam returns with mechanical precision in each generation. From the early Caliphates to the Ottoman Empire, from Khomeini's revolution to the Islamic State, from the Muslim Brotherhood to Al-Qaeda, Boko Haram, Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Islamic Republic of Iran—we are witnessing a transnational revival of the same theocratic, supremacist ideology, with the intervals between each resurgence growing dangerously shorter. This repetition is not accidental. Islamism returns not because it is hijacked or distorted but because it cannot be otherwise. An ideology that cannot change cannot die. It simply waits, regroups, and returns.

After the fall of the Ottoman Caliphate in 1924, Islamism suffered a profound symbolic and structural defeat. Throughout the early 20th century, the retrogressive, pre-modern structures of Islamic societies had rendered much of the Islamic world weak, colonized, or irrelevant on the global stage. Its resurgence began after the 1940s, fueled by petro-wealth and Western geopolitical naivety.

Islamism isn't merely a human rights crisis—it is a civilizational threat posed by the only global ideology that explicitly seeks death, martyrdom, and the annihilation of non-believers. It glorifies the afterlife—complete with the infamous 72 virgins—to such a degree that earthly existence becomes secondary, eroding the very logic of deterrence.

In Christianity, Christ returns not to conquer but to judge and to save—through grace. By contrast, Islamic eschatology is deeply political. In Sunni Islam, the arrival of the Mahdi and the return of Isa (Jesus) mark the final battles against non-Muslims—particularly Jews and Christians. The Mahdi leads a military campaign to establish global Islamic rule before the Day of Judgment. In Shia Islam, especially Twelver Shiism as espoused by the Iranian regime, the return of the 12th Imam is a messianic event that ushers in a global Islamic theocracy. In both sects, the end times are not merely spiritual—they are militarized and geopolitical, involving conquest, the elimination of disbelief, and the imposition of Sharia.

The Christian martyr dies passively, refusing to renounce faith, imitating Christ’s sacrifice—not as a strategy, but as a testimony. In Islam, however, martyrdom—primarily through Jihad—is exalted as a direct path to paradise. The martyr bypasses judgment entirely and is even said to intercede for others, creating a spiritual reward system that sanctifies violence in the name of faith.

In Christian doctrine, Jesus is the Son of God and the cornerstone of salvation. In Islam, Isa (Jesus) is a Muslim prophet who returns not to redeem but to correct. He will break the cross—symbolically rejecting Christianity—kill the Dajjal (Islam’s Antichrist) and establish Islamic law on Earth. In Islamic eschatology, Jesus does not return to save Christians but to affirm Islam and enforce its supremacy. This theological inversion is profound—yet almost entirely unknown to most Western observers.

If nuclear weapons were to fall into the apocalyptic hands of zealots like those ruling Iran, the doctrine of mutually assured destruction would be rendered impotent. How do you negotiate with those who long to die?

We are not just facing terror. We are confronting a theological machine with no off switch, no built-in mechanism for moral recalibration, and no capacity for reform.

Unlike Christianity, Islam does not separate the sacred from the secular. From its inception, it was a geopolitical project fusing law, state, and religion into one totalizing system. Thus, the term 'political Islam' is redundant, as it falsely implies the existence of a separate, non-political, spiritual Islam untouched by conquest or lawmaking—a comforting and dangerous illusion eagerly promoted by apologists and exploited by Islamists.

It is time to stop pretending that moderate Muslims can reform an immoderate doctrine. It is time to stop appeasing or funding regimes that export Islamist ideology under the guise of cultural dialogue or religious freedom. The fusion of religion and politics in Islam is not a modern deviation—it is the foundational design.

And it is this unyielding, unreformable doctrine that now stands as the greatest threat to modern civilization.

Thank you for this piece. I have tried to have such conversations with people, only to stumble on my own lack of detailed history (along with the frustration you mention!). Mind you, my husband who hitherto would offer the clichéd “Christianity is replete with barbarism” arguments, has since come round to a clearer understanding of the unyielding and violent nature of Islam.

The fall of the Ottoman Empire was a crushing and shameful blow for Islam. It seems to me that every move since then has been part of the long game - with intervals getting shorter as you say - to regaining the Caliphate. All this seems clear to me, but not to most people I speak to who think I’m paranoid at best, Islamophobic at worst.

Thanks for setting this out so clearly Maral. I think so many in the west absolutely do not understand this foundational nature of Islam. I see that many are also frightened by the violence and rhetoric that accompanies so much of Islam. They’d prefer to stick their head in the sand and hope it all “blows over” but as you describe there is zero historical precedent to suggest this. It’s important to understand it cannot in its very nature be reformed.